Using a Pact Broker to Manage Contracts Across Microservices

In the previous article, I raised an important question: What if the provider and consumer microservices do not share the same repository but still need access to the contract from a third-party source? The solution to this challenge is the Pact Broker.

In this article, we will explore how the Pact Broker works and how to implement pipeline using GitHub Actions.

When Do You Need a Pact Broker?

A Pact Broker is essential in scenarios where:

- The provider and consumer microservices are in separate repositories but must share the same contract.

- You need to manage contracts across different branches and environments.

- Coordinating releases between multiple teams is required.

Options for Setting Up a Pact Broker

There are multiple ways to set up a Pact Broker:

- Own Contract Storage Solution – Implement your own contract-sharing mechanism.

- Hosted Pact Broker (PactFlow) – A cloud-based solution provided by SmartBear.

- Self-Hosted Open-Source Pact Broker – Deploy and manage the Pact Broker on your infrastructure.

As a starting point, PactFlow is a great solution due to its ease of use.

Publishing Contracts to the Pact Broker

For demonstration purposes, we will use the free version of PactFlow. Follow these steps to publish contracts:

1. Sign Up for PactFlow

Visit PactFlow and create a free account.

2. Retrieve Required Credentials

- Broker URL: Copy the URL from the address bar (e.g.,

https://custom.pactflow.io/). - Broker API Token: Navigate to Settings → API Tokens and copy the read/write token for CI/CD pipeline authentication.

3. Setting Up a CI/CD Pipeline with GitHub Actions

Setting up CI/CD pipeline using GitHub Actions.

We will configure GitHub Actions to trigger on a push or merge to the main branch. The workflow consists of the steps displayed on the diagram.

To set up GitHub Actions, create a .yml file in the .github/workflows directory. In this example, we’ll use contract-test-sample.yml:

name: Run contract tests

on: push

env:

PACT_BROKER_BASE_URL: ${{ secrets.PACT_BROKER_BASE_URL }}

PACT_BROKER_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.PACT_BROKER_TOKEN }}

jobs:

contract-test:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: actions/setup-node@v4

with:

node-version: 18

- name: Install dependencies

run: npm install

- name: Run web consumer contract tests

run: npm run test:consumer

- name: Publish contract to PactFlow

run: npm run publish:pact

- name: Run provider contract tests

run: npm run test:providerBefore running the workflow, store the required secrets in your GitHub repository:

- Navigate to Repository → Settings → Secrets and Variables.

- Create two secrets:

- PACT_BROKER_BASE_URL

- PACT_BROKER_TOKEN

Save, commit, and push your changes to the remote repository.

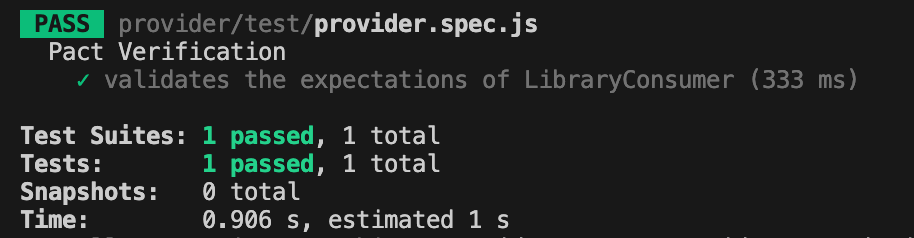

Navigate to the Actions tab in GitHub to verify if the pipeline runs successfully.

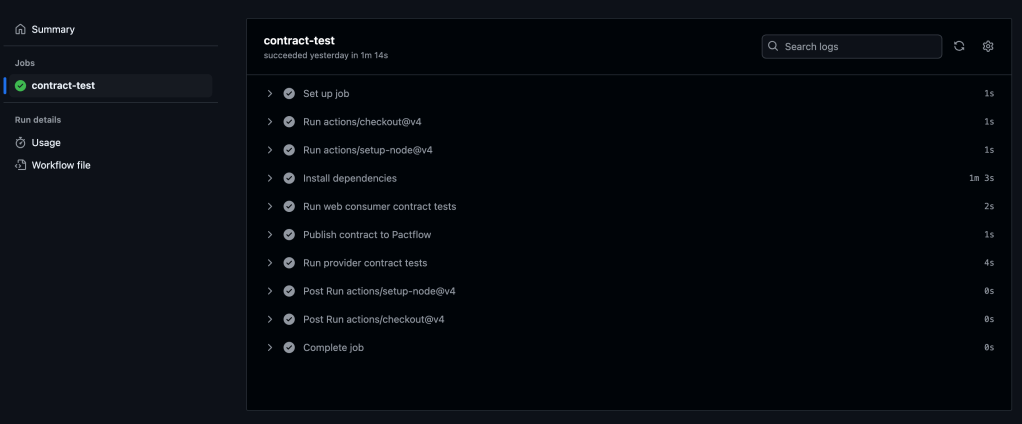

You should see all the steps running successfully like on the screenshot below:

7. Verifying the Contract in PactFlow

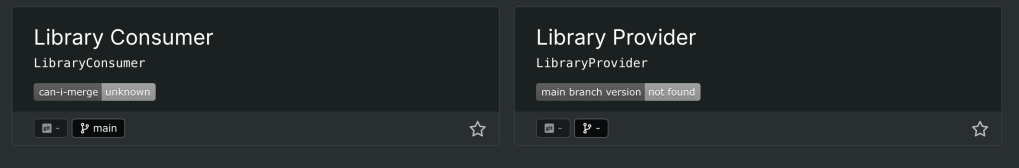

Once the pipeline runs successfully:

- Navigate to PactFlow.

- Verify if the contract has been published.

- You should see two microservices and the contract established between them.

Configuring Contract Versioning

If there are changes in the contract (e.g., if a new version of a consumer or provider is released), versioning should evolve too. Automating this process is crucial.

A recommended approach is using GitHub Commit ID (SHA), ensuring that contract versions are traceable to relevant code changes.

1. Define the Versioning Variable

In the contract-test-sample.yml file, introduce a new environment variable GITHUB_SHA:

GITHUB_SHA: ${{ github.sha }}2. Update the Pact Publish Script

Modify the pact:publish script to use the automatically generated version:

"publish:pact": "pact-broker publish ./pacts --consumer-app-version=$GITHUB_SHA --tag=main --broker-base-url=$PACT_BROKER_BASE_URL --broker-token=$PACT_BROKER_TOKEN"3. Update provider options with providerVersion value:

const opts = {

provider: "LibraryProvider",

providerBaseUrl: "http://localhost:3000",

pactBrokerToken: process.env.PACT_BROKER_TOKEN,

providerVersion: process.env.GITHUB_SHA,

publishVerificationResult: true,

stateHandlers: {

"A book with ID 1 exists": () => {

return Promise.resolve("Book with ID 1 exists")

},

},

}Configuring Branches for Contract Management

If multiple people are working on the product in different branches, it is crucial to assign contracts to specific branches to ensure accurate verification.

1. Define the Branching Variable

Add GITHUB_BRANCH to the .yml file:

GITHUB_BRANCH: ${{ github.ref_name }}2. Update the Pact Publish Script for Branching

Modify pact:publish to associate contracts with specific branches:

"publish:pact": "pact-broker publish ./pacts --consumer-app-version=$GITHUB_SHA --branch=$GITHUB_BRANCH --broker-base-url=$PACT_BROKER_BASE_URL --broker-token=$PACT_BROKER_TOKEN"3. Update provider options with providerVersionBranch value:

const opts = {

provider: "LibraryProvider",

providerBaseUrl: "http://localhost:3000",

pactBrokerToken: process.env.PACT_BROKER_TOKEN,

providerVersion: process.env.GITHUB_SHA,

providerVersionBranch: process.env.GITHUB_BRANCH,

publishVerificationResult: true,

stateHandlers: {

"A book with ID 1 exists": () => {

return Promise.resolve("Book with ID 1 exists")

},

},

}Using the can-i-deploy tool

The can-i-deploy tool is a Pact feature that queries the matrix table to verify if a contract version is safe to deploy. This ensures that new changes are successfully verified against the currently deployed versions in the environment.

Running can-i-deploy for consumer:

pact-broker can-i-deploy --pacticipant LibraryConsumer --version=$GITHUB_SHARunning can-i-deploy for provider:

pact-broker can-i-deploy --pacticipant LibraryProvider --version=$GITHUB_SHAIf successful, it confirms that the contract is verified and ready for deployment.

To reuse these commands, we will create scripts for verification in package.json file:

"can:i:deploy:consumer": "pact-broker can-i-deploy --pacticipant LibraryConsumer --version=$GITHUB_SHA"

"can:i:deploy:provider": "pact-broker can-i-deploy --pacticipant LibraryProvider --version=$GITHUB_SHA"And then update GitHub Actions pipeline:

name: Run contract tests

on: push

env:

PACT_BROKER_BASE_URL: ${{ secrets.PACT_BROKER_BASE_URL }}

PACT_BROKER_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.PACT_BROKER_TOKEN }}

GITHUB_SHA: ${{ github.sha }}

GITHUB_BRANCH: ${{ github.ref_name }}

jobs:

contract-test:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: actions/setup-node@v4

with:

node-version: 18

- name: Install dependencies

run: npm i

- name: Run web consumer contract tests

run: npm run test:consumer

- name: Publish contract to Pactflow

run: npm run publish:pact

- name: Run provider contract tests

run: npm run test:provider

- name: Can I deploy consumer?

run: npm run can:i:deploy:consumer

- name: Can I deploy provider?

run: npm run can:i:deploy:providerAdd changes, commit and push. Navigate to the Actions tab in GitHub to verify if the pipeline runs successfully.

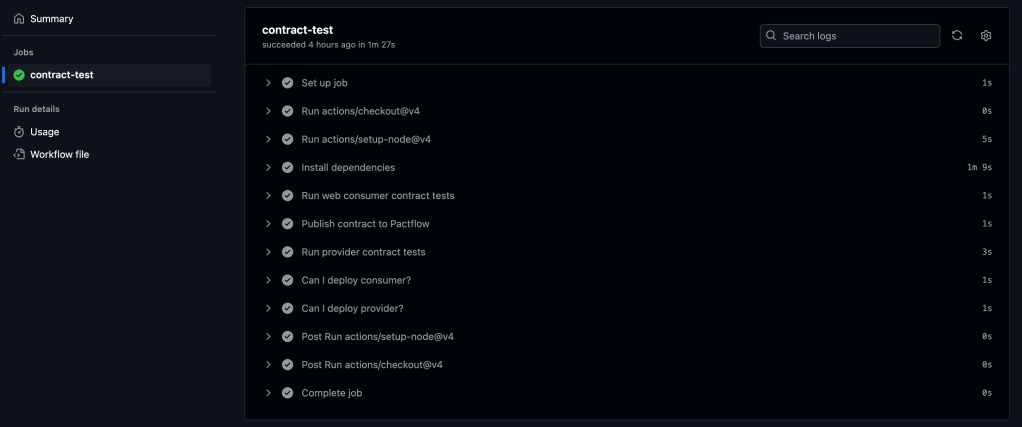

You should see all the steps running successfully like on the screenshot below:

Conclusion

The Pact Broker is important for managing contracts across microservices, ensuring smooth collaboration between independent services. By automating contract versioning, branch-based contract management, and deployment workflows using GitHub Actions, teams can can reduce deployment risks, improve service reliability, and speed-up release cycles.

For a complete implementation, refer to the final version of the code in the repository.