Introduction

This is actually my first time working with Playwright using the Model-Based Testing (MBT) approach, and I’ve been learning it recently. Honestly, it’s been a pretty cool experience! What really stood out to me is how easy it can be to test all the possible paths of your app without writing a bunch of repetitive test code. You basically define your app’s behavior in a model, and Playwright can automatically generate tests that cover everything, whether it’s valid logins or invalid ones.

I’m pretty excited about how MBT, combined with Playwright, can keep things organized, scalable, and maintainable. So, if you’re like me and just getting started with this, I’ll walk you through how I set things up, step by step, and what I learned along the way.

What is Model Based Testing?

Model Based Testing is the testing methodology that leverages model-based design for designing and executing test cases. The model represents the system’s states, the transitions between those states, the actions that trigger the transitions, and the expected outcomes.

State Machine Models

The state machine model is one of the most popular models in MBT. It represents a system in terms of its states and the transitions between them.

- States: Represent various configurations or conditions of the system.

- Transitions: Describe the movement between states, triggered by specific events or actions.

- Actions: Input or conditions that cause a transition from one state to another.

This type of the model suits the systems with discrete states (e.g. login flow, traffic lights, etc.). It is simple to understand and visualize.

Example: Login Flow

Let’s consider a simple login form with two fields (Email and Password) and a Submit button.

When the user submits the login form, the system checks the credentials and triggers the SUBMIT action. If the credentials are valid (user@example.com and password), the system transitions from the formFilledValid state to the success state, displaying the “Welcome!” message. However, if the credentials are invalid, the system transitions from the formFilledInvalid state to the failure state, displaying the “Invalid credentials.” message.

- States

Definition: Represent various configurations or conditions of the system.

In the login machine, the states are:

idle:

- The initial state when the login form is first loaded.

- In this state, the email and password fields should be visible.

formFilledValid:

- Represents the state when the form is filled out with valid credentials (user@example.com / password).

formFilledInvalid:

- Represents the form being filled with invalid credentials (wrong@example.com / wrongpass).

success:

- A final state indicating successful login (e.g., “Welcome!” message is shown).

failure:

- A final state indicating login failure (e.g., “Invalid credentials.” message is shown).

- Events/Actions

Definition: Inputs or conditions that cause a transition from one state to another.

These are the inputs sent to the machine that trigger transitions:

- FILL_FORM: Filling the form with valid data.

- FILL_FORM_INVALID: Filling the form with invalid data.

- SUBMIT: Submitting the login form (used in both valid and invalid paths).

- Transitions

Definition: Describe the movement between states, triggered by specific events.

The transitions in this case are:

- Transition 1: From the formFilledValid state to the success state, triggered by the SUBMIT action when the credentials are correct.

- Transition 2: From the formFilledInvalid state to the failure state, triggered by the SUBMIT action when the credentials are incorrect.

You can find this example in the GitHub repository. Here’s how it looks:

Login Flow with XState

Now, let’s model this login flow with a state machine using XState.

XState is a state management and orchestration solution for JavaScript and TypeScript apps.

Refer to official documentation on how to start and create a machine.

Install xstate and xstate/test. XState is used to define the state machine logic, while @xstate/test allows us to generate tests automatically based on the defined model. This reduces boilerplate and ensures consistency between model and tests.

npm install xstate @xstate/testImport the necessary xstate libraries into your spec file:

import { createMachine } from "xstate";

import { createModel } from "@xstate/test";Create a state machine:

import { createMachine } from 'xstate';

import { expect } from '@playwright/test';

export const loginMachine = createMachine({

id: 'login',

initial: 'idle',

states: {

idle: {

on: {

FILL_FORM: 'formFilledValid',

FILL_FORM_INVALID: 'formFilledInvalid'

},

meta: {

test: async ({ page }) => {

await expect(page.getByPlaceholder('Email')).toBeVisible();

await expect(page.getByPlaceholder('Password')).toBeVisible();

}

}

},

formFilledValid: {

on: {

SUBMIT: 'success'

},

meta: {

test: async ({ page }) => {

const email = await page.getByPlaceholder('Email');

const password = await page.getByPlaceholder('Password');

await expect(email).toHaveValue('user@example.com');

await expect(password).toHaveValue('password');

}

},

},

formFilledInvalid: {

on: {

SUBMIT: 'failure'

},

meta: {

test: async ({ page }) => {

const email = await page.getByPlaceholder('Email');

const password = await page.getByPlaceholder('Password');

await expect(email).toHaveValue('wrong@example.com');

await expect(password).toHaveValue('wrongpass');

}

}

},

success: {

type: 'final',

meta: {

test: async ({ page }) => {

const msg = await page.locator('#message');

await expect(msg).toHaveText('Welcome!');

}

}

},

failure: {

type: 'final',

meta: {

test: async ({ page }) => {

const msg = await page.locator('#message');

await expect(msg).toHaveText('Invalid credentials.');

}

}

}

}

});Key Parts of the State Machine:

States:

- idle: Initial state when the form is empty, waiting for user input.

- formFilledValid: State after the form is filled with valid credentials.

- formFilledInvalid: State after the form is filled with invalid credentials.

- success: Final state when the user has successfully logged in.

- failure: Final state when the login fails due to incorrect credentials.

Transitions:

- FILL_FORM: Transition that occurs when the user fills out the form correctly.

- FILL_FORM_INVALID: Transition when the user fills out the form with invalid credentials.

- SUBMIT: Transition that occurs when the user submits the form.

You can visualize this model using XState Visualizer or Stately, which automatically generates a graphical representation of your state machine, making it easier to understand and communicate the flow.

Meta properties

The meta properties define assertions or checks that validate whether the state machine has transitioned successfully between states.

!! Important to highlight that meta properties themselves do not involve actions or events (like clicking buttons or submitting forms). They are purely for validating if the system has reached a specific state.

Example: In the idle state, we should assert that the form’s input fields (Email and Password) are visible and present on the page. This ensures that the system is in the correct state and ready to receive user input:

meta: {

test: async ({ page }) => {

await expect(page.getByPlaceholder('Email')).toBeVisible();

await expect(page.getByPlaceholder('Password')).toBeVisible();

}

}Add your tests

Creating the tests is super easy since we let xstate generate our test plans for us. The snippet below basically generates the tests dynamically based on the model.

- Create a test model with events

import { createModel } from '@xstate/test';

import { loginMachine } from './loginMachine';

import { Page } from '@playwright/test';

type TestContext = { page: Page };

async function fillForm(context: TestContext, email: string, password: string) {

const { page } = context;

await page.locator('#email').fill(email);

await page.locator('#password').fill(password);

}

const testModel = createModel(loginMachine).withEvents({

FILL_FORM: async (context: unknown) => {

const { page } = context as TestContext;

await fillForm({ page }, 'user@example.com', 'password');

},

FILL_FORM_INVALID: async (context: unknown) => {

const { page } = context as TestContext;

await fillForm({ page }, 'wrong@example.com', 'wrongpass');

},

SUBMIT: async (context: unknown) => {

const { page } = context as TestContext;

await page.getByRole('button', { name: 'Login' }).click();

}

});2. Iterate through available test paths and execute test cases.

import { test } from '@playwright/test';

test.describe('Login Machine Model-based Tests', () => {

test.beforeEach(async ({ page }) => {

await page.goto('http://localhost:3000');

});

const testPlans = testModel.getShortestPathPlans();

for (const plan of testPlans) {

for (const path of plan.paths) {

test(path.description, async ({ page }) => {

await path.test({ page });

});

}

}

test('should cover all paths', async () => {

testModel.testCoverage();

});

});The full code snippet:

import { test, Page } from '@playwright/test';

import { createModel } from '@xstate/test';

import { loginMachine } from './loginMachine';

type TestContext = { page: Page };

async function fillForm(context: TestContext, email: string, password: string) {

const { page } = context;

await page.locator('#email').fill(email);

await page.locator('#password').fill(password);

}

const testModel = createModel(loginMachine).withEvents({

FILL_FORM: async (context: unknown) => {

const { page } = context as TestContext;

await fillForm({ page }, 'user@example.com', 'password');

},

FILL_FORM_INVALID: async (context: unknown) => {

const { page } = context as TestContext;

await fillForm({ page }, 'wrong@example.com', 'wrongpass');

},

SUBMIT: async (context: unknown) => {

const { page } = context as TestContext;

await page.getByRole('button', { name: 'Login' }).click();

}

});

test.describe('Login Machine Model-based Tests', () => {

test.beforeEach(async ({ page }) => {

await page.goto('http://localhost:3000');

});

const testPlans = testModel.getShortestPathPlans();

for (const plan of testPlans) {

for (const path of plan.paths) {

test(path.description, async ({ page }) => {

await path.test({ page });

});

}

}

test('should cover all paths', async () => {

testModel.testCoverage();

});

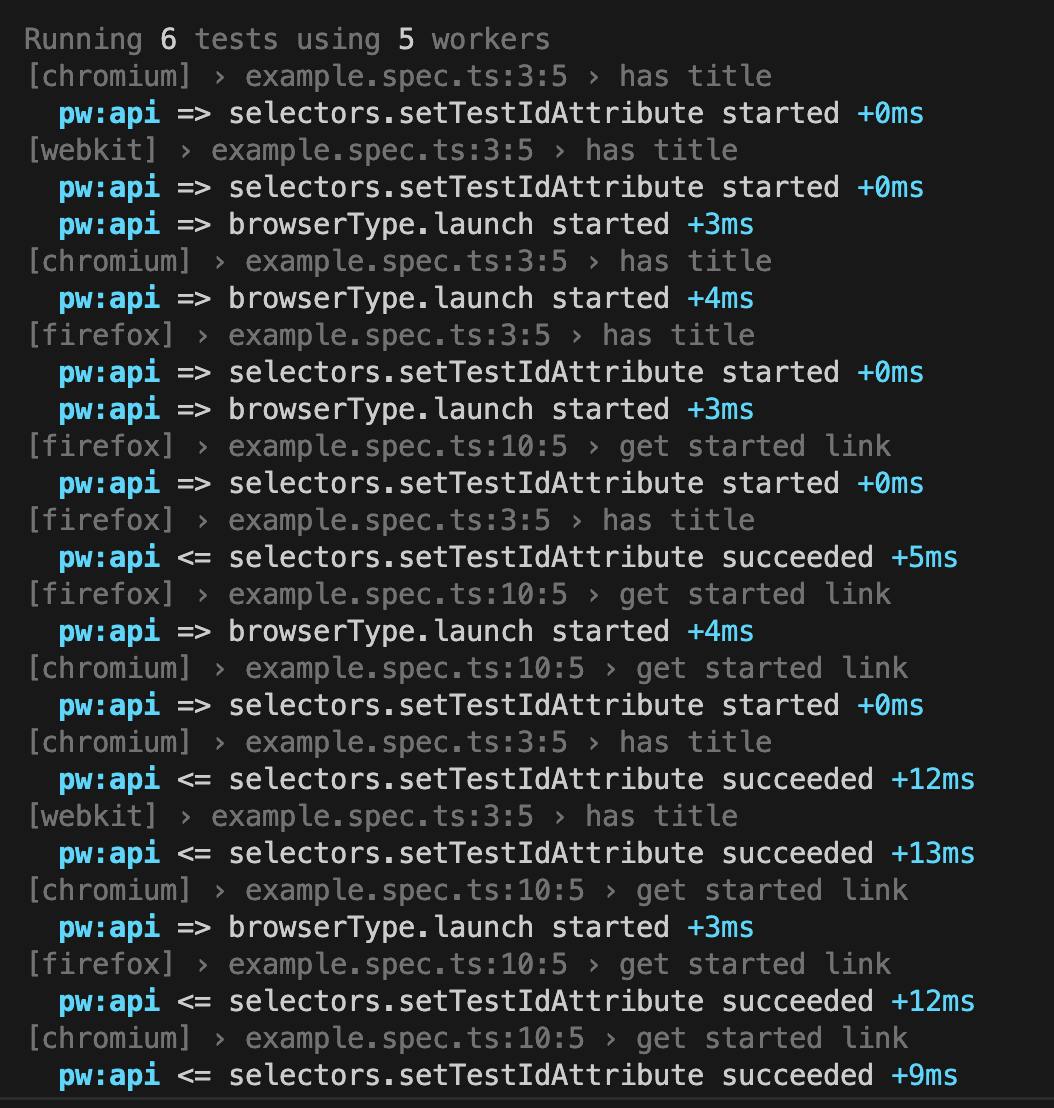

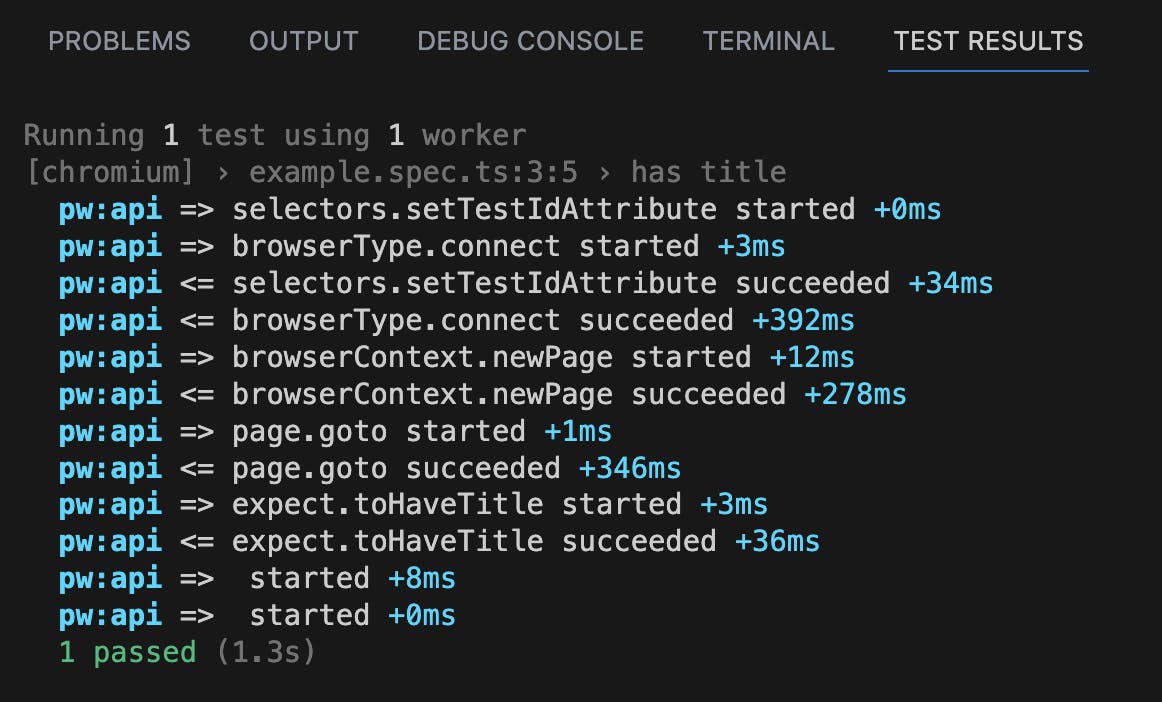

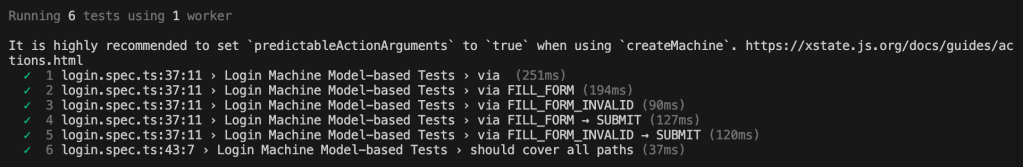

});Execute Test Cases

To run test cases, execute this command:

npx playwright testAs a result, all the paths will be derived and executed:

What can be done even better.

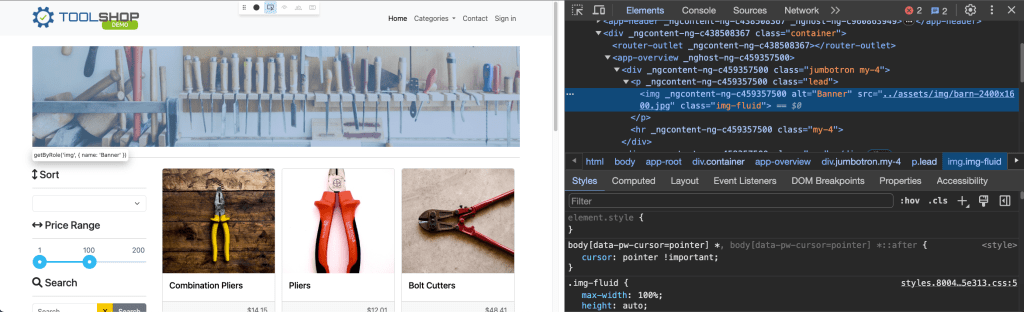

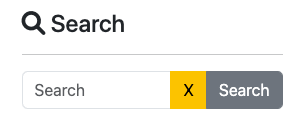

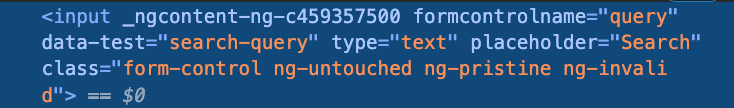

Consider the two snippets below, which demonstrate two different approaches to identifying the same element (an email input field):

- Using the id attribute:

const email = await page.locator('#email');2. Using the getByPlaceholder() method:

const email = await page.getByPlaceholder('Email');While both methods work, they introduce unnecessary variability in locator strategies. This can lead to confusion.

To avoid this inconsistency, we can introduce a more structured way to define and reuse locators. One effective approach is to adopt the Page Object Model (POM) pattern.

Advantages of Model-Based Testing approach

- Ensures all possible user paths (valid/invalid logins) are tested. With a proper model, you’ll never forget a test case again! Every valid and invalid login, every happy path and error state, it’s all there, mapped out.

- One model defines both behavior and tests, easy to update. This is a huge win. Once you’ve got your model, it doubles as both a behavior map and a test generator. So when the app changes, you just tweak the model.

- Tests are generated automatically from the model. This is absolute magic. The model can automatically produce test cases, helping you focus on designing better logic instead of managing test scripts.

- State diagrams help explain app behavior clearly. These diagrams aren’t just for testers, they’re great for showing developers, designers, and even PMs how the app behaves. Everyone can see the “big picture”.

- Encourages thinking through logic before coding. You’re forced (in a good way!) to plan how the system should behave before jumping into code.

Disadvantages of Model-Based Testing approach

- More effort than needed for simple flows. If you’re testing a basic login form or something tiny, setting up a full model might feel like overkill. The setup time pays off for complex systems, but not always for quick one-off tests.

- Requires understanding XState and state machines. Here is a bit of a learning curve. If you are new to the concept of states, transitions and actions, you definitely need to spend some time to understand it, but with practice it gets easier.

- The model must stay in sync with the actual UI. As soon as the UI changes, it needs a bit of discipline to align it with the existing model.

- Harder to model non-deterministic flows. Some parts of an app (like random data, unpredictable user input, or flaky network calls) can be tricky to represent in a model.

Conclusion

Model-Based Testing with Playwright and XState is a super powerful way to keep your tests organized, maintainable, and easy to scale. By turning your app’s behavior into a state machine, you can automatically generate tests that cover all the possible paths, no more wondering if you missed something. This approach really shines when you’re working with flows that have clear steps, like login forms, authentication, or multi-step processes. It’s all about making testing smarter, not harder!

Resources:

- Repository with source code.

- Another perspective from Erik Van Veenendaal, internationally recognized testing expert and author of a number of books.